The Beauty of Japanese Traditional Construction Method Houses: Zairai Kouhou Explained

2025年09月29日

Explore Zairai Kouhou, Japan’s revered traditional construction method. This article delves into its unique post-and-beam structure, natural materials, and historical significance, explaining why these homes offer exceptional earthquake resistance, natural comfort, and sustainability, connecting residents to nature and heritage.

目次

Understanding Zairai Kouhou: The Japanese Traditional Construction Method

What is Zairai Kouhou

Zairai Kouhou (在来工法), often translated as the “conventional,” “traditional,” or “ordinary” construction method, refers to the time-honored techniques used in building traditional Japanese houses and structures. This method is fundamentally characterized by its wooden post-and-beam framework, where the entire weight of the building is supported by an intricate system of vertical columns and horizontal beams.

Unlike many Western construction methods that rely on load-bearing walls, Zairai Kouhou emphasizes a flexible wooden skeleton. This allows for open, adaptable interior spaces that can be reconfigured using sliding doors and screens, rather than fixed walls.

Key Elements of Zairai Kouhou:

- Kigumi (木組み): A highly sophisticated system of traditional wood joinery. Kigumi techniques connect wooden components without the need for nails, screws, or other metal fasteners. These intricate, interlocking joints are not merely aesthetic; they are engineered to absorb and disperse seismic vibrations, making the structures remarkably resilient in earthquake-prone Japan. There are over 200 distinct Kigumi joint types, each meticulously crafted to leverage the natural properties of wood.

- Daiku (大工): The master carpenters who are central to Zairai Kouhou. These skilled artisans possess a profound understanding of wood characteristics, joinery techniques, and traditional Japanese aesthetics. Often acting as both architect and builder, a Daiku’s expertise ensures the precision and longevity of a Zairai Kouhou structure.

- Natural Materials: Traditional Japanese construction predominantly utilizes locally sourced natural materials such as various types of wood (including Japanese cypress and cedar), bamboo, and earth. Earthen walls, known as tsuchikabe, are common, featuring a lattice framework coated with layers of earth. These walls contribute to the building’s durability and flexibility.

- Ishibatate (Raised Foundations): A distinctive feature where wooden columns rest directly on flat stone foundations (ishibatate) rather than being rigidly fastened to the ground. This “floating” foundation allows the entire building to shift cohesively during an earthquake, reducing stress on the structure. Furthermore, elevating the floor several tens of centimeters above ground helps prevent moisture ingress and promotes natural ventilation, crucial in Japan’s humid climate.

A Brief History of Japanese Traditional Houses

The evolution of Japanese traditional architecture is a rich tapestry woven with indigenous innovations and influences from mainland Asia, adapting over centuries to Japan’s unique climate, seismic activity, and cultural sensibilities.

Early Japanese architecture, dating back to the Jomon period (14,000–300 BCE), began with simple pit dwellings. The Yayoi period (300 BCE–300 CE) saw the emergence of raised-floor structures, likely influenced by practices from the Korean Peninsula, which helped protect homes from dampness and improved ventilation.

The introduction of Buddhism to Japan during the Asuka period (538–710 CE) was a pivotal moment, leading to large-scale temple construction and the refinement of timber joinery techniques (Kigumi). The Horyu-ji Temple, completed in 607 AD, stands as the world’s oldest surviving wooden structure, a testament to the durability of these early methods.

During the Nara period (710–794 CE), urban planning flourished, and many palace and temple buildings adopted the architectural styles of China’s Tang dynasty.

However, it was during the Heian period (794–1185 CE) that a distinctly Japanese architectural style, known as Shinden-zukuri (寝殿造), truly blossomed. This style characterized the grand mansions of the aristocracy, featuring a symmetrical layout, open interior spaces, and interconnected buildings linked by covered corridors. Shinden-zukuri emphasized harmony with nature, incorporating gardens and ponds, and utilized sliding panels to allow for flexible spatial arrangements.

As the warrior class gained prominence in the Kamakura (1185–1333 CE) and Muromachi (1338–1573 CE) periods, a new style emerged: Shoin-zukuri (書院造). Influenced by Zen Buddhism, Shoin-zukuri evolved from Shinden-zukuri and introduced features that became foundational for modern traditional Japanese homes. These included square posts, floors entirely covered with tatami mats, built-in desks (tsuke-shoin), recessed alcoves (tokonoma) for displaying art, and staggered shelves (chigai-dana).

The Azuchi-Momoyama (1573–1603 CE) and Edo (1603–1868 CE) periods saw the development of Sukiya-zukuri (数寄屋造). This style drew heavily from the aesthetics of traditional tea houses (chashitsu), prioritizing simplicity, natural materials, and a refined, understated beauty known as wabi-sabi. Sukiya-zukuri offered greater design freedom than its predecessors and became popular for residences, inns (ryokan), and restaurants, with notable examples like the Katsura Imperial Villa.

While the Meiji Restoration (1868 CE onwards) brought significant Western architectural influences, leading to hybrid construction styles, the principles and aesthetics of Zairai Kouhou continue to be cherished. There is a renewed appreciation for these traditional methods due to their eco-friendliness, resilience, and longevity.

| Period | Architectural Style | Key Characteristics | Influence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heian (794–1185 CE) | Shinden-zukuri (寝殿造) | Symmetrical layout, open plans, interconnected buildings, sliding partitions, integration with gardens. | Aristocratic mansions, development of “Kokufu bunka” (Japanese culture). |

| Kamakura & Muromachi (1185–1573 CE) | Shoin-zukuri (書院造) | Tatami-covered floors, square posts, tokonoma (alcove), chigai-dana (staggered shelves), built-in desks. | Samurai residences, Zen Buddhist influence, foundation for modern traditional houses. |

| Azuchi-Momoyama & Edo (1573–1868 CE) | Sukiya-zukuri (数寄屋造) | Simplicity, natural materials, refined aesthetics (wabi-sabi), derived from tea houses, greater design freedom. | Residences, inns (ryokan), restaurants. |

Key Characteristics of Zairai Kouhou Houses

The Post and Beam Structure

At the heart of Zairai Kouhou, the Japanese traditional construction method, lies its distinctive post and beam structure. This system relies on a robust framework of vertical posts (columns) and horizontal beams to support the entire building, a fundamental difference from Western load-bearing wall constructions. This architectural approach allows for significant flexibility in interior layouts, enabling large, open-plan spaces and the installation of expansive windows that connect the interior with the surrounding environment.

Historically, these pillars were often set upon foundation stones without being rigidly fixed, allowing for a degree of movement during seismic activity. However, modern Zairai Kouhou has evolved to incorporate contemporary engineering, typically utilizing concrete foundations and often employing bolts and metal plates to securely fasten the posts and beams, providing enhanced stability and earthquake resistance. The standard dimensions for pillars in Zairai Kouhou are commonly around 120 by 120 millimeters.

Innovative Joinery and Connections

One of the most remarkable features of Zairai Kouhou is its sophisticated system of traditional Japanese joinery, often referred to as Kumiki. These intricate woodworking techniques enable the interlocking of wooden components without the extensive use of nails, screws, or other metal fasteners. This mastery of wood allows for the creation of incredibly strong and stable structures that can withstand the test of time and natural forces.

There are over 200 types of Kumiki techniques, broadly categorized into tsugite, which connect wood pieces vertically to lengthen them, and shiguchi, used for joining pieces at right angles or diagonally. These precision-crafted joints offer several advantages: they allow the structure to flex and absorb seismic energy, contributing to earthquake resistance; they facilitate the disassembly and reconstruction of buildings; and they enable the replacement of rotten or damaged wood sections. While traditional joinery remains a cornerstone, contemporary Zairai Kouhou may also integrate modern metal-fastener joints to meet current building codes and enhance structural integrity.

Natural Materials and Their Benefits

Wood Types Used in Traditional Japanese Construction

Japan’s abundant forests have historically provided the primary building material for Zairai Kouhou houses: wood. The selection of specific wood types is crucial, chosen for their inherent strength, durability, aesthetic appeal, and natural properties that contribute to a healthy living environment. The most commonly utilized woods include:

| Wood Type | Key Characteristics | Traditional Uses |

|---|---|---|

| Hinoki (Japanese Cypress) | Light yellowish-white, distinctive lemon-like aroma, high resistance to insects and rot, excellent durability, beautiful gloss. Kiso Hinoki is a particularly prized variety. | Temples, palaces, shrines, Noh theaters, baths, and high-end furniture. |

| Sugi (Japanese Cedar) | Japan’s national tree, sturdy light reddish-brown, good decay resistance, soft with low density, fragrant, weather and insect resistant. | Load-bearing structures, outdoor projects, pillars, ceiling boards, and even bathtubs and kitchen cabinets due to anti-mold qualities. |

| Akamatsu (Japanese Red Pine) | Good hardness and elasticity, highly resistant to water and rot, straight grain, medium texture, oily feel. | Construction lumber, beams in religious buildings, and outdoor projects. |

| Keyaki (Japanese Zelkova) | Extremely hard, tough, highly resistant to wear and decay, beautiful and prized grain. | Main pillars of temples, shrines, and castles, due to its strength and aesthetic value. |

Earthen Walls and Their Role

Earthen walls, known as tsuchikabe (土壁) or dobei (土塀), are another integral natural material in Zairai Kouhou, contributing significantly to the comfort and sustainability of traditional Japanese homes. These walls are typically constructed from a mixture of local clay, sand, straw, and water, often reinforced with a lattice of bamboo laths called komai.

The benefits of earthen walls are multifaceted. They play a crucial role in regulating indoor humidity by absorbing excess moisture on damp days and releasing it when the air is dry, thus creating a more stable and comfortable interior climate. Furthermore, their thermal mass provides a moderating effect on daily temperature fluctuations, helping to keep interiors cooler during hot Japanese summers and warmer in winter. Earthen walls also offer excellent sound insulation and are 100% recyclable, underscoring the sustainable nature of Zairai Kouhou. The exterior surfaces are often finished with a thin layer of lime-based plaster, known as shikkui, which provides protection from rain and contributes to the aesthetic appeal.

Adaptation to Japan’s Climate and Environment

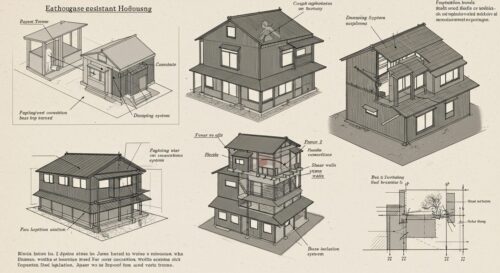

Zairai Kouhou houses are ingeniously designed to harmonize with Japan’s unique climate and environmental challenges, particularly its seismic activity and high humidity. The flexible nature of the post-and-beam structure, combined with the intricate joinery, allows the entire building to sway and absorb the energy of earthquakes rather than rigidly resisting them, thereby enhancing disaster resistance. Modern Zairai Kouhou further bolsters this resilience with concrete foundations and diagonal bracing.

To combat Japan’s often humid climate, traditional Zairai Kouhou incorporates features that promote superior ventilation. Elevated floors allow air to circulate beneath the house, while open floor plans and strategically placed large windows facilitate natural airflow throughout the interior. Natural materials like wood and earthen walls inherently contribute to humidity regulation, absorbing and releasing moisture to maintain a comfortable indoor environment. Deep eaves are a characteristic architectural element that effectively shields external walls from strong summer sunlight and heavy rain, while also allowing ample natural light to filter into the home. This thoughtful design not only ensures comfort but also fosters a deep aesthetic connection to nature, often incorporating views of gardens and the surrounding landscape into the living space.

The Enduring Advantages of Japanese Traditional Construction Method Houses

Earthquake and Disaster Resistance

Superior Ventilation and Comfort

Aesthetic Appeal and Connection to Nature

Sustainability and Longevity

| Aspect | Traditional Zairai Kouhou | Modern Construction (Typical) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Materials | Wood, earth, paper, straw (e.g., for tatami) | Concrete, steel, plastics, gypsum board |

| Renewability | Highly renewable (wood from managed forests) | Often relies on non-renewable resources (minerals, fossil fuels) |

| Embodied Energy | Relatively low due to minimal processing | Generally higher due to industrial production |

| Durability/Lifespan | Centuries (with ongoing maintenance and repair) | Decades (often designed for shorter cycles in Japan) |

| Repairability | High (individual components can be replaced) | Can be complex, often requires specialized parts or demolition |

| Waste/Recyclability | Biodegradable, reusable materials | Significant waste, difficult recycling for composite materials |

| Humidity Control | Natural material breathability (e.g., earthen walls, wood, tatami) | Often relies on mechanical HVAC systems and vapor barriers |

Modern Interpretations and Challenges for Zairai Kouhou

Integrating Traditional Japanese Construction into Contemporary Design

The timeless principles of Japanese traditional construction, or Zairai Kouhou, continue to profoundly influence contemporary architectural design in Japan and globally. Modern architects are adept at blending traditional aesthetics with modern functionality, creating spaces that resonate with a deep connection to nature and a sense of calm.

Key elements frequently integrated into contemporary designs include open floor plans, which foster a sense of spaciousness and natural light, and a seamless connection to outdoor gardens and landscapes. The use of natural materials, especially wood, remains central, reflecting the enduring philosophy of working in harmony with the environment.

Architects like Kengo Kuma are recognized for their innovative approach, integrating traditional culture with modern technology by employing bi-dimensional elements that act as filters or connections between the interior and exterior. Similarly, Yoshiji Takehara reinterprets traditional spatial concepts to redefine indoor-outdoor relationships in modern residences. His strategies include clustered building layouts, multi-directional openings, and visual links to courtyards, along with transitional spaces such as corridors and doma (earthen-floored transitional zones).

Traditional features like shoji screens are reimagined as movable walls, offering flexibility in space configuration while modulating light and shadow, and providing privacy without blocking natural light. This adaptability and emphasis on efficient use of space and climate adaptation are hallmarks of traditional Japanese design that continue to inform sustainable building practices today.

Balancing Tradition with Modern Building Codes

While Zairai Kouhou offers numerous advantages, its application in modern construction faces the critical challenge of complying with Japan’s stringent building codes, particularly those related to seismic resistance, fire safety, and insulation. Japan, being highly prone to earthquakes, has some of the most robust anti-seismic standards in the world.

The Zairai Kouhou method itself has evolved from older Dento-koho, which relied on the flexibility of non-fixed structures. Modern Zairai Kouhou incorporates Western architectural know-how, featuring posts and beams secured with metal bolts and plates, and diagonal braces within walls. Crucially, contemporary Zairai Kouhou homes are built on concrete foundations that firmly secure the structure to the ground, aiming to resist seismic shocks with a firm structure rather than absorbing energy through deformation.

For existing traditional buildings, specific technical methods are employed for preservation and seismic retrofitting. These strategies often involve reinforcing existing structural elements, adding new walls, and fitting seismic dampers.

The table below outlines common seismic retrofitting methods used to enhance the resilience of traditional Japanese homes:

| Retrofit Method | Description | Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Concrete Foundation Work | Strengthening or installing continuous concrete strip foundations to anchor the wooden structure firmly. | Prevents the house from shifting off its foundation during an earthquake. |

| Reinforcing Walls with Braces | Adding diagonal braces (tasuki-gake) within wall frames or reinforcing existing ones. | Increases the shear strength and stiffness of the structure. |

| Seismic Dampers | Installing connecting-type visco-elastic dampers or spring systems in walls. | Absorbs seismic energy and increases damping capacity without compromising structural flexibility. |

| Base Isolation (Menshin) | Employing laminated rubber bearings and dampers at the base of the structure. | Allows the building to move horizontally during seismic activity, significantly reducing stress on the structure. |

Beyond seismic concerns, older traditional homes often lack adequate insulation, leading to higher energy consumption. Modern renovations address this by upgrading insulation in walls, floors, and ceilings with sustainable materials like cellulose or recycled denim, and by installing double-glazed windows to improve thermal performance.

The Future of Japanese Traditional Construction Method Houses

Despite the rise of modern construction techniques, Zairai Kouhou continues to be the preferred method for approximately 80% of newly built homes in Japan, largely due to its design flexibility, efficiency, and cost-effectiveness. The future of Japanese traditional construction is characterized by a concerted effort to preserve its invaluable heritage while adapting to contemporary needs and technological advancements.

A crucial aspect is the preservation of traditional skills and knowledge, particularly those held by master carpenters, known as Daiku. Organizations like Hanbara are dedicated to safeguarding these techniques through apprenticeship programs, ensuring that the intricate art of Japanese carpentry, including its unique joinery (kigumi), is passed down to future generations. The Takenaka Carpentry Tools Museum also plays a vital role in collecting and conserving traditional tools and reintroducing Daiku culture, which faced decline in the latter half of the 20th century.

The global interest in sustainable and resilient housing further highlights the relevance of Zairai Kouhou. Its emphasis on natural, locally sourced materials and designs that harmonise with the environment positions it as a model for sustainable architecture worldwide. Government incentives and subsidies in Japan also encourage seismic-safe construction and retrofitting, supporting the longevity and safety of these homes.

Technological advancements are also contributing to the future of Zairai Kouhou, with ongoing research and analysis of traditional structures to understand and enhance their performance, especially in seismic events. The continuous evolution of building codes, such as the revised 2×4 building code effective in April 2025, reflects an ongoing commitment to integrating wood construction into modern urban landscapes, including mid-rise buildings.

Conclusion

The Japanese Traditional Construction Method, or Zairai Kouhou, stands as a testament to centuries of architectural wisdom, deeply rooted in Japan’s unique climate, seismic activity, and cultural reverence for nature. Far from being a relic of the past, this enduring building technique continues to shape contemporary Japanese residential architecture, remaining the preferred method for a significant percentage of newly built homes today. Its principles offer invaluable lessons for sustainable and resilient construction worldwide.

At its core, Zairai Kouhou is defined by its robust post-and-beam framework, meticulously crafted using innovative joinery techniques that often forgo metal fasteners in favor of precise wood-on-wood connections. This flexible structural system, combined with traditional stone foundations known as ishibatate, allows buildings to “dance” with seismic forces rather than rigidly resist them, effectively dissipating earthquake energy and demonstrating remarkable resilience, as evidenced during the 1995 Great Hanshin Earthquake.

Beyond its structural integrity, Zairai Kouhou champions a profound connection to the natural world. The reliance on locally sourced, natural, and biodegradable materials such as Japanese cedar (sugi), cypress (hinoki), earthen walls (tsuchikabe), and rice straw tatami mats ensures superior breathability, natural insulation, and minimal environmental impact. These elements contribute to a comfortable indoor environment, naturally regulating humidity and temperature, while fostering an aesthetic that seamlessly blends with the surrounding landscape.

While deeply traditional, Zairai Kouhou is not static. Modern interpretations have successfully integrated contemporary design elements and building codes, sometimes incorporating metal fasteners and concrete foundations to enhance structural integrity and efficiency, while preserving the inherent design flexibility and spaciousness characteristic of the method. The ongoing scientific validation of traditional techniques continues to bridge the gap between ancient wisdom and modern engineering, ensuring the method’s continued evolution and relevance.

In an era increasingly focused on environmental responsibility and disaster preparedness, the enduring advantages of Japanese traditional construction method houses resonate more strongly than ever. Zairai Kouhou offers a holistic model for building that prioritizes harmony with nature, structural resilience, and long-term sustainability. It serves as a powerful reminder that the wisdom of the past holds profound solutions for the challenges of the future.

The table below summarizes the enduring advantages of Zairai Kouhou:

| Aspect | Traditional Zairai Kouhou Advantage |

|---|---|

| Resilience | Flexible post-and-beam structure, intricate joinery, and stone foundations (ishibatate) provide exceptional earthquake and disaster resistance. |

| Sustainability | Utilizes natural, renewable, and biodegradable materials like wood, earth, and rice straw, minimizing environmental footprint. |

| Comfort | Promotes superior natural ventilation and humidity regulation, creating a healthy and comfortable indoor living environment. |

| Aesthetics | Offers timeless beauty, a harmonious integration with nature, and a deep connection to Japan’s rich cultural heritage. |

| Longevity | Constructed for durability and adaptability, allowing homes to endure for generations with proper maintenance and care. |

Our Home Building Videos