From Tradition to Modernity: Why Japanese Houses Are Built to Withstand Earthquakes

2025年12月23日

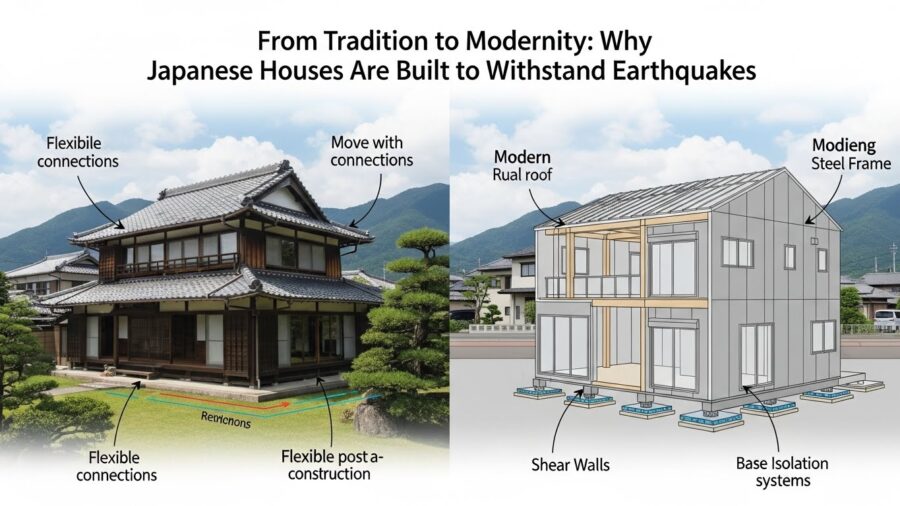

Japan is situated along the volatile Pacific Ring of Fire, making earthquake resistance not merely a feature of construction but a fundamental necessity for survival. The resilience of Japanese houses is the result of a unique convergence between centuries of traditional architectural wisdom and rigorous modern engineering standards. This article explores the structural secrets that allow these buildings to withstand powerful tremors, revealing that the answer lies in a strategic balance of flexibility, material choice, and strict legal regulations.

Readers will gain a comprehensive understanding of how Japanese architecture has evolved from the vibration-absorbing timber frameworks of ancient temples to the advanced base isolation systems found in contemporary homes. We will examine the critical role of the 1981 Amendment to the Building Standards Act, a legislative turning point that established the high safety benchmarks defining the modern real estate market. By uncovering the mechanics behind traditional techniques like the Shinbashira central pillar and nail-free Kigumi joinery, alongside modern damping technologies, you will understand why Japanese houses are designed not to rigidly resist nature, but to move in harmony with it to ensure lasting safety.

目次

The Evolution of Seismic Design in Japanese Architecture

Japan’s architectural history is inextricably linked to its geography. Located along the Pacific Ring of Fire, the archipelago experiences approximately 1,500 earthquakes annually. This constant geological threat has forced Japanese builders to evolve from merely constructing shelters to engineering sophisticated structures capable of surviving violent ground motion. Unlike Western architecture, which historically favored the rigidity of stone and brick, Japanese builders cultivated a philosophy of resilience through flexibility, utilizing wood as their primary medium to harmonize with, rather than resist, nature’s forces.

Ancient Wisdom of Wooden Pagodas and Temples

The resilience of traditional Japanese architecture is best exemplified by its wooden pagodas, particularly the five-story pagoda at Horyu-ji Temple. Built in the 7th century, it is recognized as one of the world’s oldest surviving wooden structures. Despite enduring centuries of typhoons and massive earthquakes, not a single one of Japan’s historic multi-story pagodas has ever collapsed due to seismic activity alone.

This survival is not accidental but the result of ancient structural wisdom. Builders understood that a rigid structure would snap under the intense lateral forces of an earthquake. Instead, they designed pagodas as a series of stacked, independent floors. During a tremor, these floors move independently of one another, a phenomenon often described as a “snake dance.” This alternating movement counteracts the swaying of the building, preventing the resonance that typically destroys tall structures. While modern science later quantified these mechanics, the ancient master carpenters (miyadaiku) intuitively grasped that survival required a structure to move with the earth.

The Role of Flexibility in Traditional Timber Frameworks

The core principle of traditional Japanese seismic design is flexibility. In the evolution of the Japanese house (minka), timber was chosen not just for its abundance, but for its high strength-to-weight ratio and ductility. Unlike stone or masonry, which are brittle and prone to cracking, wood can bend and warp significantly before breaking.

Traditional timber frameworks were designed to act as shock absorbers. The structural integrity relied on a post-and-beam construction method that allowed the entire building to deform slightly during an earthquake. This deformation absorbs the kinetic energy of the quake, dissipating it through the friction of wood-on-wood joints and the flexing of the pillars. This concept stands in stark contrast to the rigid “box” construction of modern Western housing, where the goal is often to prevent any movement at all. In traditional Japanese design, a building that could sway was a building that would stand.

From Rigid Stones to Modern Concrete Foundations

One of the most significant evolutionary shifts in Japanese residential architecture lies in the foundation. Historically, Japanese houses were built using the Ishiba-date method. In this traditional approach, wooden pillars were not fixed to the ground but simply rested on top of large, flat stones. There were no bolts or concrete anchors connecting the structure to the earth.

This design functioned as a primitive form of seismic isolation. When a strong earthquake struck, the pillars could slide or even “hop” across the stones. This sliding motion effectively decoupled the house from the ground’s violent shaking, reducing the seismic energy transferred to the upper structure. However, following the modernization of Japan and the implementation of stricter building codes—especially after the 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake—construction methods shifted toward securing structures to the ground.

Modern Japanese houses now utilize reinforced concrete foundations with pillars firmly bolted down. While this prevents the house from collapsing or shifting off its base, it fundamentally changes the seismic dynamic: the structure must now be strong enough to resist the full force of the ground motion rather than evading it. This evolution highlights a transition from the philosophy of “avoidance” to one of “resistance,” driving the development of the advanced engineering techniques seen today.

| Feature | Traditional (Ishiba-date) | Modern (Reinforced Concrete) |

|---|---|---|

| Connection to Ground | Free-standing; pillars rest on stones | Anchored; pillars bolted to concrete |

| Seismic Response | Sliding and hopping (Base Isolation) | Resistance and absorption (Rigidity) |

| Energy Transfer | Minimizes energy transfer to the frame | Transfers ground energy directly to the frame |

| Primary Risk | Displacement from foundation | Structural failure of walls/pillars |

For more on the historical context of these structures, the UNESCO World Heritage Centre provides detailed records on the Buddhist Monuments in the Horyu-ji Area.

Key Structural Secrets Behind Earthquake Resistant Japanese Houses

The Shinbashira Central Pillar and Vibration Control

Kigumi Joinery Techniques That Absorb Seismic Energy

| Feature | Traditional Kigumi (Joinery) | Modern Metal Fasteners |

|---|---|---|

| Connection Type | Interlocking wooden geometry | Nails, bolts, and plates |

| Seismic Response | Flexible; absorbs energy through friction | Rigid; resists force until failure |

| Material Behavior | Wood compresses and expands naturally | Metal may rust or split the wood |

| Restorability | Joints can often be re-tightened | Fasteners may require replacement |

Why Wood Is Preferred Over Stone in Seismic Zones

Modern Engineering and the 1981 Building Standard Amendment

While traditional carpentry provided the foundation for seismic safety in Japan, the modern era brought rigorous legal standards and advanced engineering to the forefront. The turning point for Japanese construction occurred with the 1981 Amendment to the Building Standards Act. Known as the Shin-Taishin (New Seismic Standards), this legislation fundamentally shifted the philosophy of building safety from merely preventing damage to ensuring human survival during catastrophic events.

Triggered by the damage caused by the 1978 Miyagi Earthquake, the new standards mandated that buildings must not only withstand moderate earthquakes (JMA intensity 5) with minimal damage but also prevent collapse during massive earthquakes (JMA intensity 6 to 7). This shift has proven effective; data from the 1995 Great Hanshin Earthquake showed that buildings constructed under the Shin-Taishin standards suffered significantly less damage than those built under the old regulations.

The Shift from Earthquake Resistance to Seismic Isolation

In the decades following the 1981 amendment, Japanese engineering evolved beyond simple “resistance.” Engineers realized that while making a building rigid (Resistance) prevents collapse, it does not necessarily stop violent shaking inside, which can cause furniture to topple and injure occupants. This led to the development of Vibration Control and Base Isolation technologies.

Today, modern Japanese architecture generally utilizes one of three distinct seismic strategies. The following table outlines the differences between these key technologies:

| Method | Japanese Term | Mechanism | Seismic Effect | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Earthquake Resistance | Taishin (耐震) | Reinforcing walls, pillars, and beams to create a rigid structure that withstands force. | Prevents collapse, but shaking is directly transferred to the interior. | Standard for most detached houses and low-rise buildings. |

| Vibration Control | Seishin (制震) | Installing dampers (oil, rubber, or viscous) within the structure to absorb kinetic energy. | Reduces swaying by 20–50%, minimizing structural damage. | High-rise condos and increasingly common in modern wooden homes. |

| Base Isolation | Menshin (免震) | Separating the building from the ground using isolators (e.g., laminated rubber bearings). | Drastically reduces shaking (up to 66-80%) by preventing energy transfer. | Skyscrapers, hospitals, and high-end residential properties. |

Understanding Base Isolation Systems in Residential Homes

Base Isolation, or Menshin, is widely considered the pinnacle of earthquake engineering. Unlike traditional methods that anchor the house directly to the foundation, base isolation places the entire structure on top of flexible devices—typically laminated rubber bearings or sliding sliders—that absorb and dissipate the ground’s movement.

When a major earthquake strikes, the ground beneath may shake violently, but the house itself glides gently on top of the isolators. This decoupling means that the intense seismic energy is not transferred to the building frame. For residents, the difference is stark: while a standard house might experience violent jolts that throw furniture across the room, a base-isolated home often experiences only a slow, gentle swaying motion. Although Menshin is the most expensive option, adding 10–20% to construction costs, it is increasingly adopted in luxury homes and critical infrastructure where preserving the interior and functionality is paramount.

Damping Technologies Used in Contemporary Housing

Bridging the gap between standard resistance and expensive isolation is Vibration Control, or Seishin. This technology has become a popular upgrade for modern wooden houses in Japan. It involves installing damping devices—similar to the shock absorbers in a car—into the structural frame of the walls.

These dampers are often made using viscous oil, high-damping rubber, or friction materials. When an earthquake distorts the building frame, the dampers stretch and compress, converting the kinetic energy of the quake into heat energy and dissipating it. This process not only reduces the amplitude of the swaying but also shortens the duration of the shaking. By reducing the stress on the wooden joints and structural panels, Seishin technologies help prevent the “cumulative damage” that can occur from repeated aftershocks, ensuring the house remains safe not just for one major event, but for the lifetime of the building.

For further reading on Japan’s construction regulations, the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism (MLIT) provides resources on building standards and disaster prevention.

Conclusion

The exceptional earthquake resistance of Japanese houses is not the result of a single discovery but rather a millennia-long evolution that harmonizes ancient craftsmanship with cutting-edge engineering. From the flexible, interlocking timber frames of historic temples to the sophisticated base isolation systems in modern residences, the approach to seismic safety in Japan has always been dynamic and adaptive. The resilience of these structures lies in a deep understanding of the forces of nature—choosing to work with the tremors rather than rigidly opposing them.

While traditional architecture relied on the natural flexibility of wood and the ingenuity of Kigumi (joinery) to absorb energy, modern Japanese housing integrates these principles with rigorous scientific standards. The amendment of the Building Standard Law in 1981 marked a pivotal shift, ensuring that contemporary homes are built not just to prevent collapse, but to protect human life and minimize structural damage during catastrophic events. Today, the fusion of the Shinbashira concept—seen in the Tokyo Skytree—with advanced damping technologies illustrates how Japan continues to look to its past to secure its future.

Summary of Seismic Strategies: Traditional vs. Modern

To understand why Japanese houses stand firm, it is essential to recognize how historical methods have translated into modern applications. The following table outlines the transition and adaptation of key seismic defense mechanisms.

| Feature | Traditional Approach

(Ancient Wisdom) |

Modern Application

(Engineering & Technology) |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Philosophy | Flexibility (Ju-no-ri): Allowing the building to sway and deform slightly to absorb shock without breaking. | Isolation & Damping: Decoupling the structure from the ground or using hydraulic dampers to dissipate kinetic energy. |

| Key Mechanism | Shinbashira (Central Pillar): Acts as a pendulum to counterbalance structural vibration, commonly seen in pagodas. | Mass Damper Systems: Heavy counterweights or fluid dampers installed in high-rises and homes to reduce sway. |

| Joinery & Connections | Kigumi (Interlocking Wood): Wood-on-wood joints that tighten during tremors and allow for restoration. | Metal Brackets & Bolting: Reinforced steel plates and braces that secure joints against high-tensile forces. |

| Foundation | Ishiba-date (Stone Base): Pillars rest on stones, allowing the building to “jump” or slide off to prevent snapping. | Reinforced Concrete: Deep mat foundations and piles that anchor the house firmly or support isolation bearings. |

The Legacy of the 1981 Building Standard Amendment

The structural integrity of modern Japanese homes is heavily indebted to the strict regulatory environment established by the government. The “New Anti-Seismic Design Standards” (Shin-Taishin) introduced on June 1, 1981, fundamentally changed the construction landscape. Unlike pre-1981 structures, which were designed primarily to withstand moderate tremors (JMA intensity 5), post-1981 houses are engineered to prevent collapse even during massive earthquakes (JMA intensity 6-7). This regulatory framework is continuously updated, incorporating lessons learned from disasters such as the Great Hanshin Earthquake and the Great East Japan Earthquake.

Homeowners and buyers in Japan now prioritize these standards, often seeking “Long-life Quality Housing” certifications that exceed the basic legal requirements. This systemic commitment to safety ensures that the knowledge gained from every seismic event is immediately codified into the built environment.

Future Perspectives on Seismic Safety

As technology advances, the definition of a “strong house” in Japan continues to expand. The current trend is moving beyond mere survival (Earthquake Resistance) toward livability and functionality post-disaster (Seismic Isolation and Vibration Control). Innovations such as cross-laminated timber (CLT) are bringing the flexibility of wood back into high-rise construction, proving that the preference for timber is not just nostalgic but scientifically sound.

Ultimately, Japanese houses are earthquake-resistant because they represent a culture of preparedness. It is a unique architectural ecosystem where the wisdom of the carpenter meets the precision of the computer simulation, ensuring that when the ground shakes, the home remains a sanctuary.

For further reading on the specific regulations that govern these structures, you can refer to the overview provided by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism.